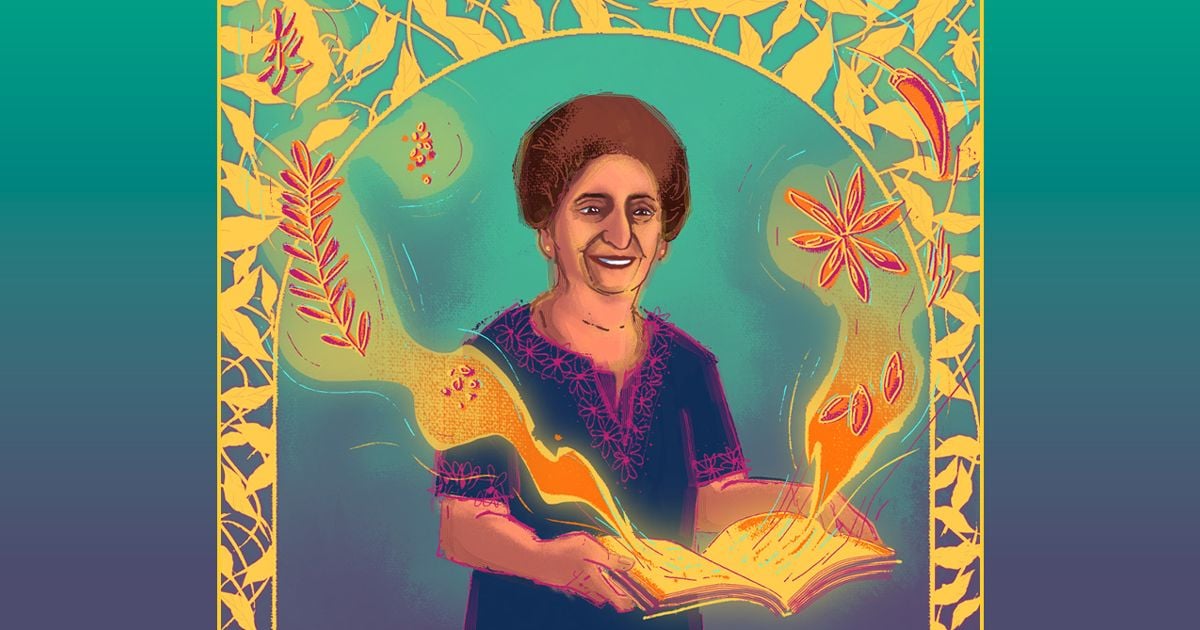

Noorbanu Nimji was a culinary force who taught fans around the world about the Indian and East African food of her Ismaili Muslim heritage.

In 2016, Western Living magazine announced its annual Foodies of the Year list. It featured a typical selection of cutting-edge chefs and beverage masters, but among the honourees was also the oldest person ever named to the list, as well as the only home cook recognized that year: an eightysomething Calgary grandmother named Noorbanu Nimji.

Five years later, it’s clear that Nimji’s presence on Western Living’s list—where she received the title of “Reluctant Icon”—was a fitting nod to her unique place in the Canadian food world. Nimji, who passed away last June at age 85, spent more than 40 years teaching fans around the world about the Indian and East African food of her Ismaili Muslim heritage through A Spicy Touch, a self-published cookbook series that went on to sell several hundred thousand copies. From her home kitchen, she served as a one-woman cultural council, ensuring that multiple generations of Ismailis could learn about and appreciate their homelands. “When the time comes [and] our parents and grandparents are no longer around, how do we preserve that heritage aspect of our cooking?” says Ali Jadavji, a Calgary chef who grew up near the Nimji family. Through her recipes and her commitment to teaching the next generation, “Mrs. Nimji did that for us.” Nimji’s journey from homemaker to culinary celebrity started when she and her family arrived in Canada from Nairobi, Kenya, in 1974. As a young wife and mother, she learned to cook dishes that blended her Gujarati heritage and the cuisines of East Africa: potato curry, pigeon peas and savoury rice dishes.

After Ugandan president Idi Amin called for the expulsion of Asians from the country in the early 1970s, Nimji’s family left Kenya, worrying the same might happen there. Many Ismailis, who are part of a Shia Muslim community currently led by Prince Karim al-Husayni (Aga Khan IV), sought asylum in Canada, the U.K. and elsewhere, leading to the creation of a diaspora that now spans 25 countries. Today, there are about 100,000 Ismailis living in Canada.

In Calgary, the Nimjis were active in the local Ismaili community, and it was common for Noorbanu to host visiting Ismailis for dinner at home, often to rave reviews and requests to learn how to make the samosas, spice mixes and condiments she served. None of her recipes were written down, so she would have people come over to teach them how to make bharazi (pigeon peas in coconut cream) or kuku paka (chicken, potatoes and eggs in coconut sauce), says her son, Akbar Nimji. “And that’s how it started.”

“It” was Nimji’s foray into recording her recipes and teaching them to others in a more formal setting, starting with small cooking classes for university students in the late 1970s. The classes, which met every Saturday in Nimji’s home kitchen, were organized by local Ismaili community members for those students who wanted a taste of home but had no idea how to make the comfort food they craved.

She quickly amassed enough codified Indian and Indo–East African recipes for her first cookbook, A Spicy Touch: Volume 1, published in 1986. Getting the book to print was a family affair: A teenage Akbar was in charge of typing all his mother’s handwritten notes, which often included terms in Gujarati, Swahili and Arabic. The final product almost didn’t see the light of day when Nimji found out how expensive it would be to have it printed. But after a home-cooked meal, the representative from the company struck a deal: They would front the money for the initial costs, and Nimji would reimburse them once copies sold.

And sell they did. Following the initial success of the first volume, Nimji released a second in 1992 and a third in 2007. The first three volumes sold more than 250,000 copies, especially remarkable considering the first two books were only available for purchase in Canada during the 1980s and 1990s. Many were given to new brides across the diaspora who had either never been to their family’s homelands or had not lived there long enough to learn traditional dishes. Through word of mouth, the book became a precious culinary and cultural resource. Nimji’s role as a community connector showcases the importance of food as a cultural touchstone in diasporas, says Nazira Mawji, an educator whose doctoral dissertation focused on Ismaili women’s experiences in Canada.

“When families were leaving the last place of settlement where they came from, there was very little they could take with them in comfortable in a strange land,” says Mawji. “One of those most important aspects was food. If they could make the food, they could turn any place into their homeland. Food was not only something that made a new place of settlement into home, but it was also a way [for] of gaining independence within the family, being important within the family and also a way of earning a living.” In a few short years, Nimji went from being a homemaker catering small community parties to a local celebrity that all Calgarians wanted to learn from. She hosted cooking demonstrations at local community centres, at a store in downtown Calgary called the Cookbook Company and at the Calgary Stampede, where she funded the annual Ismaili-Canadian pancake breakfast that featured bharazi-stuffed mandazi (coconut doughnuts). She also hosted her own events. Whether she was on stage or in the crowd, she always patiently answered questions from visitors about recreating a certain restaurant dish at home, explaining that not all curries were spicy and offering Indian-style options for preparing Alberta beef.

“Even when we were trying to [land] the name ‘A Spicy Touch’ . . . I could get that the general Caucasian population could be scared of spicy food,” says Akbar. Without TV coverage of Indian food or the internet’s trove of how-to videos, Nimji became a guide for many non-Ismailis who wanted to add a spicy touch to their diets.

One of those people was Karen Anderson, a nurse who took her first cooking class with Nimji in the 1990s. Anderson was drawn to her teacher’s humility and impeccable cooking skills.

“One of the biggest things she taught me was tasting, tasting, tasting along the way to educate your palate,” she says. Anderson became a devoted student of Nimji’s and eventually co-authored the fourth volume of A Spicy Touch with her: A Spicy Touch: Family Favourites from Noorbanu Nimji’s Kitchen, published in 2015 as a best-of collection from Nimji’s archive, with new recipes from family and friends. The book was received with praise in the food world, receiving silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards and for Best Regional/Cultural Cookbook at the Taste Canada Awards. In addition to her spot on Western Living’s Foodies of the Year list, she also received positive coverage in the Globe and Mail and on CBC.

“As a devoted friend, to see somebody who worked their whole life never expecting any recognition be recognized, that was really fulfilling for me,” says Anderson, who took over many of the promotional duties of the book due to Nimji’s failing health. “[Noorbanu] was quietly thrilled by the awards.”

But even as she wound down her public appearances in the last years of her life, Nimji’s goal of preserving her community’s traditions was wrapped up in every samosa and stirred into every fragrant sauce. Eating one of Nimji’s dishes was like participating in “history that she made, and that her mother made for her, and that her mother’s mother made for her,” says Akbar. “That’s the legacy that she wanted: that [our] people should not forget who they really are.”

This story was originally published in 2021; updated in 2022

GET CHATELAINE IN YOUR INBOX!

Subscribe to our newsletters for our very best stories, recipes, style and shopping tips, horoscopes and special offers.

Source link