Thanksgiving is an American holiday rooted, in myth and in practice, around the table. The emotion that underpins the day — gratitude for life’s bounty — is not unique to the United States, even if some of the trappings are, starting with the giant oven-roasted turkey in the middle of the dinner table.

Many first-generation immigrants to America can’t help but eyeball the bird with skepticism, no matter how much they want to adopt the customs of their new home. Turkeys — often hulking specimens, hard to cook, rather bland — are not native to many countries around the world. Compared with the complex, multilayered dishes of Italy or Lebanon or West Africa, a Butterball turkey blasted to 180 degrees can be (how to say this delicately?) underwhelming to the holiday’s newcomers.

Take Vito Rago, father of Rossella Rago, the host of “Cooking With Nonna,” a sweet, Old World-paced online series dedicated to homestyle Italian cooking. From the day he set foot in America from his native Puglia in southern Italy, Vito adapted a hard line against Thanksgiving turkey. His daughter remembers that, on the holiday in her childhood home, the turkey wouldn’t go into oven until 1 p.m., so that it was ready around 9:30 p.m., well after the parade of Italian American dishes had already been inhaled.

The turkey was “like a decoration” to her father, Rossella jokes. “If it were plastic, it would be fine to him.”

Vito may have been more active in keeping the turkey down, but other immigrants, or their offspring, share in his distaste. “I am not a big fan of turkeys,” Lebanese native and cookbook author Joumana Accad emailed from Beirut, where she moved after living in the United States for more than 30 years.

“I’m not a turkey fan,” echoed chef and author Pierre Thiam, a native of Senegal.

“I didn’t always like turkey!” noted Raj Thandhi, founder of the lifestyle blog Pink Chai Living and a first-generation daughter of Indian immigrants.

Immigrants who came from Latin American countries, as you might expect, have a different take on a bird that has a long history in the cuisines of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

“A lot of people do the perfunctory Thanksgiving turkey,” says Maricel Presilla, a chef, historian and author. “They go through the motions of having the bird because they want it to be pretty like in the glossy magazines. But they don’t really like turkey. I happen to love turkey. I love it. I absolutely love turkey.”

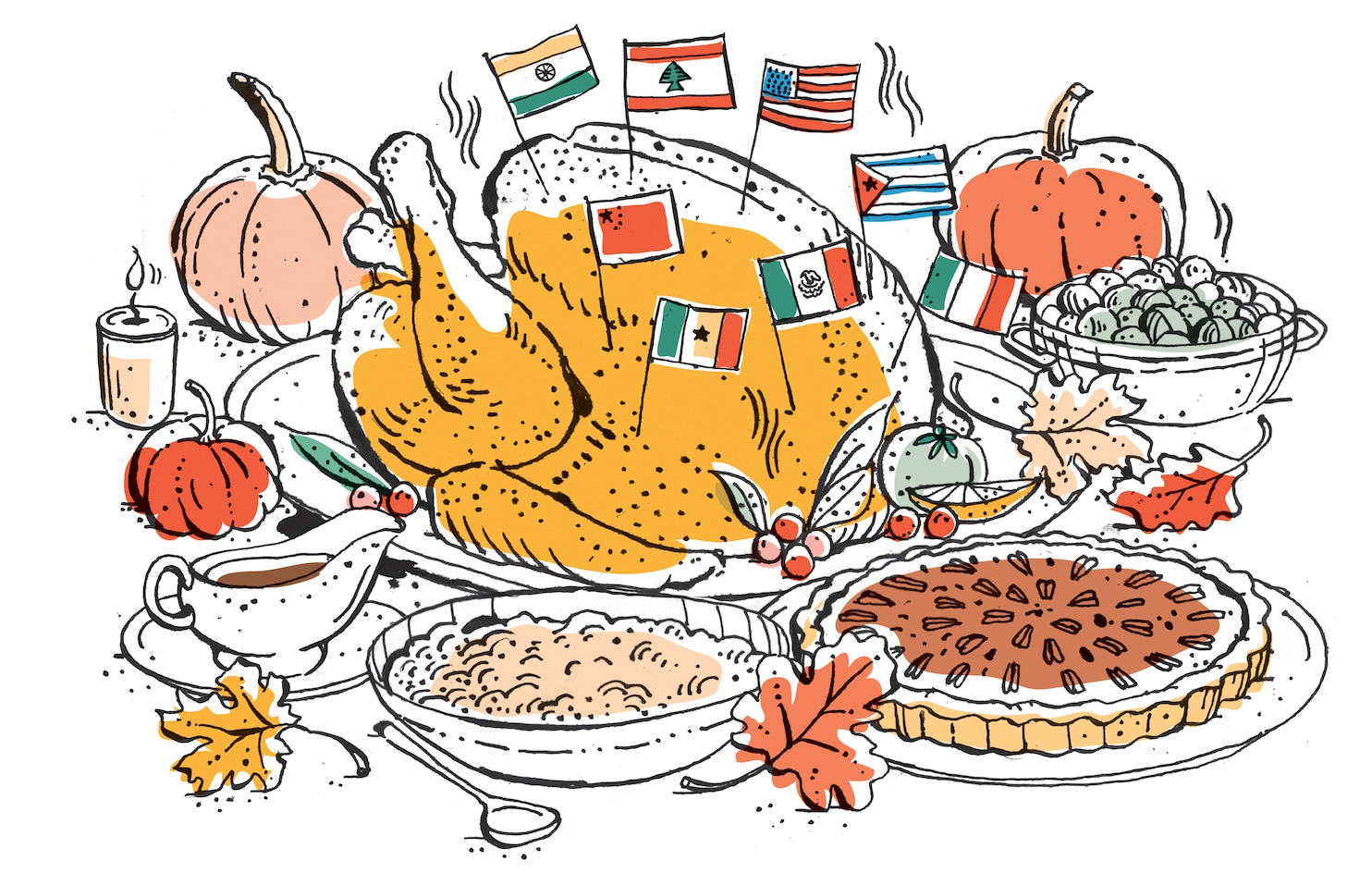

But regardless of their ancestral land, newcomers to the United States often identify with Thanksgiving, and for the holiday spread, they’ll frequently dip into the pantry of their mother country to modify the bird of their adopted country. Which is how you end up with Peking-style turkey, tandoori turkey, tamarind and honey-glazed turkey and countless other recipes that prove the American melting pot can be found in the kitchen, too.

The Thanksgiving holiday resonates for many immigrants, Presilla says.

“Everybody, in a way, that’s outside of their country is like a pilgrim,” she adds. “Pilgrim in the true sense of the word: You leave everything behind, and you reinvent yourself in a different country.”

Here are seven short stories about how immigrants or their children transformed the Thanksgiving turkey.

Rossella Rago

As a first-generation Italian American, Rago couldn’t help but notice how well Italians had assimilated into the United States — except, she says, on Thanksgiving, when everyone had to prove they were more Italian than their neighbors. The family might enjoy two different lasagnas before the turkey ever made an appearance on the table. But a few years ago, Rago’s mother-in-law, Maria Pesce, decided to introduce the turkey earlier in the meal, in an attempt to marry the Old World and the New World on Thanksgiving. Even her Thanksgiving Citrus Turkey recipe was a fusion: It incorporated flavors from the old country, including olive oil, garlic, rosemary, sage, navel orange, lemon and pinot grigio. Rago faithfully reproduced it in her cookbook “Cooking With Nonna: A Year of Italian Holidays.” So did the Italian-style turkey persuade Rago’s dad to try a bite of the bird? Not a chance, Rago says. “He doesn’t eat it,” she says. “He looks at it.”

Pierre Thiam

Tamarind and Honey-Glazed Roast Turkey

For the past few years, Thiam has been developing an American market for fonio, an ancient grain that is versatile, gluten-free and, perhaps most important, resistant to the drought conditions faced by West African farmers who grow the grasses. Though on a much smaller scale, Thiam’s Tamarind and Honey-Glazed Roast Turkey follows a similar path: It introduces Americans to some of the signature flavors in thieboudienne, Senegal’s national dish, which in turn encourages West African immigrants to embrace turkey, a bird rarely eaten in their native land. When Thiam developed the recipe for Saveur, he knew he wanted to include tamarind. After all, some think Dakar, Thiam’s hometown, was named after the Wolof word for the tamarind tree. From there, he added fish sauce and Scotch bonnet peppers for umami, fruitiness and a small element of heat. The result? Even for non-turkey eaters, the chef says, “you see people coming back for seconds.”

Recipe: Tamarind and Honey-Glazed Roast Turkey

Joe Ng

Born in Hong Kong, Ng moved to Brooklyn with his family when he was a teenager. Ed Schoenfeld, Ng’s business partner in RedFarm, says his publicity-shy chef has always had an interest in blending cultures with his food. You’ll see it with Ng’s egg rolls, which come stuffed with ruby-red slices of pastrami from Katz’s Delicatessen. Or with his campy take on Cantonese har gow dumplings, which he has shaped into Pac-Man ghosts, complete with beady eyes. For Thanksgiving diners at RedFarm, Ng has created, arguably, his masterpiece: a turkey prepared like the Peking duck he serves at sister restaurant Decoy. The techniques and the flavorings (soy sauce, star anise, hoisin, ginger and more) are virtually the same for both birds, down to pumping them with air to separate the skin from the meat. The Peking-style turkey comes with, among other things, housemade Chinese pancakes, hoisin sauce, shredded scallions, pickled shallots and — wait for it — cranberry sauce. “You could call it a hybridization,” Schoenfeld says. “But Chinese food adapts to different cultures all over the world.”

Raj Thandhi

In the 1980s, when Thandhi was a child in Surrey, British Columbia, her father worked for a nearby lumber mill that, every year, gave its employees a coupon for a free turkey to celebrate Canadian Thanksgiving. Thandhi’s mother dutifully learned to cook it, even though turkey was not an ingredient common to her native Punjab state. “We always thought turkey was dry, and we covered it with gravy,” Thandhi recalls. Fast forward to 2017. Thandhi, now founder of Pink Chai Media and a mother of two, decided to host a Friendsgiving dinner. She was determined to prepare a turkey that would honor her Indian heritage but still respect the Canadian holiday (which Thandhi says is similar to the American one, except it’s in October and no one watches football). Thus was born her Tandoori Turkey, which she rubs with a yogurt-based marinade that includes chili powder, garam masala, fenugreek leaves, black salt, ginger and garlic and more. It was a huge hit. It was also the ideal protein for her friends, who have different dietary restrictions based on their religion. “Turkey is nondenominational,” Thandhi says. The Tandoori Turkey is something of a birthday present, too: Thandhi was born on Oct. 12, 1980, which happened to fall on Canadian Thanksgiving that year.

Adán Medrano

Chile Ancho Roast Turkey With Adobo

Born in San Antonio, Medrano was a child with a foot in both Mexican and American culture. His family would regularly drive to Nava, Coahuila, a small town in Mexico, not far from the Rio Grande, where relatives owned a pecan orchard. Turkey was a routine part of his diet, and not just on Thanksgiving. Not surprisingly, Medrano has a taste for the bird. “I eat turkey sandwiches,” he writes via email. “I think it also tastes great with chiles.” Medrano is something of a polymath: He’s a filmmaker, a trained chef, a culinary historian and a cookbook author. (His latest is “Don’t Count the Tortillas.”) For his turkey, he created a recipe that draws on family history: Ancho, he says, was “the principal chile that my mom used,” especially for the holidays. But Medrano also wanted to do to turkey what cooks have done to tortillas for generations: flavor it with chile. “Infuse the tortilla with chile, and it becomes tortilla enchilada. Infuse the turkey with chile, and it becomes guajolote enchilado,” or turkey enchilado, he says. Guajolote enchilado is “made during the Christmas season by some Mexican families.”

Joumana Accad

Roast Turkey With Spicy Rice Stuffing

Born and raised in Beirut, Accad lived in Paris and Southern California before settling in Dallas, which she still considers her “hometown.” Even though she lived for 32 years in the United States, she always managed to find others to cook the turkey for Thanksgiving. She instead would focus on desserts or Lebanese mezze, dishes that would take on more importance when she shifted careers later in life to become a baker and blogger. But when she was working on her “Taste of Beirut” cookbook, Accad took on the challenge of creating a Lebanese-style turkey, which turned out to be barely a challenge at all. “It was an easy jump, because the traditional meal in Lebanon for Christmas (or a big celebration) was a roasted chicken with spiced rice, and soup. I switched the turkey for the chicken,” she emails. The Lebanese twist has more to do with the stuffing than the bird itself. The rice, fragrant with nutmeg, cardamom and allspice, is combined with a ground-meat-and-onion mixture frequently used to fill kibbe balls. From there, all you have to do is place your roast turkey on a platter and surround it with the spiced rice, along with assorted nuts. “I have taken the American tradition of the Thanksgiving turkey and given it the Lebanese treatment,” she says.

Maricel E. Presilla

Roast Turkey in Andean Pepper and Pisco Adobo

Thanksgiving holds special meaning in the Presilla household. In 1970, Presilla and her family had fled Cuba and were staying with relatives in Miami when they celebrated their first Thanksgiving. Except Presilla was in no mood to celebrate. The teenager missed her former life, and she missed her boyfriend, Alejandro. Presilla was washing dishes from the meal when she received a call: It was from Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Soldiers had picked up Alejandro as he swam across the bay. At the base, he would also enjoy his first Thanksgiving meal. Alejandro and Maricel would later become husband and wife, and she would even later become a chef and an expert on Latin American foodways, culminating with her 900-plus-page masterwork, “Gran Cocina Latina.” One of the book’s featured dishes is Roast Turkey in Andean Pepper and Pisco Adobo, a recipe that incorporates not just the brandy but also mirasol peppers, cumin, garlic, cilantro and other flavors of the Peruvian table. Presilla serves the bird with roasted plantains and sweet potatoes, a Latin American variation on candied yams. It’s a sweet touch for a holiday that is “about family and memory,” she says, and about “giving thanks to be in a country that has accepted me and has allowed me to thrive.”

Illustrations by Kat Chadwick. Design and Art Direction by Emma Kumer.

Source link