Introduction

Since the blooming of the so-called “Green Revolution” post World War II, the quest for agricultural productivity (Patel, 2013) has led to the loss of food biocultural diversity as well as to an overall standardization of the world foodscape (Bégin, 2016), driven by the industrialization of food production (Clapp, 2012). In reaction to this change, a new understanding started to take shape in the late 1980’s, aimed at rescuing and promoting traditional and local varieties as well as at preserving food and gastronomic heritage. While the first signs of this inclination emerged in the wine industry in the late 60’s, when European legislation about origin certification was designed and enforced (Addor and Grazioli, 2002), it was only in the 1980’s that a new attention to local food products started to spread. Specifically, in the Global North, customers changed their attitudes toward food, giving more attention to the quality of products, their methods of production, their origin as well as to their characteristics linked to regional identity and sensory qualities (Ilbery et al., 2005; Tregear et al., 2007). At the same time, interest in these products was characterized by an ethical and environmental footprint (Murdoch et al., 2000), a new awareness that appears to challenge the hegemony of commercial, mass-produced food (Guptill et al., 2016) fostering new forms of production and consumption as a way to build more democratized, socially just and environmentally sustainable food systems (Allen, 2010; Sage, 2011). This phenomenon has in turn fostered the revival of food heritage; the set of material and immaterial elements of food cultures (e.g., agricultural products, ingredients, dishes, techniques, recipes, and food traditions) that are considered a shared legacy or a common good in a given geographical and sociocultural context (Bessière, 1998).

Consumers are interested in the origin and production methods of food. However, local places of consumption are essential for conveying products and their associated values to final consumers. In this sense, the catering sector has played a pivotal role in building bridges between urban customers and rural producers from peripheral areas (Timothy and Ron, 2013; Rinaldi, 2017). In fact, several restaurants in Europe and North America have contributed to the rediscovery of neglected food and recipes (Pereira et al., 2019), to the promotion of local gastronomic heritage (Miele and Murdoch, 2002) as well as to the reinvigoration of the economic and cultural resources of specific regions (Broadway, 2015). As far as Western countries are concerned, a further dimension of the revival of traditional foods entails a re-territorialization strategy through the creation of stronger networks among the restaurants and a whole set of local food-related actors (Ilbery and Maye, 2005; Lane, 2011). The growing demand for traditional and local products has fostered the purchase of artisanal and seasonal produce directly from local and regional suppliers (Martinez et al., 2010) and more recently the development of projects aimed at the self-production of such products in restaurant gardens and farms (De Chabert-Rios and Deale, 2018).

Restaurateurs have begun to purchase local and traditional food products, as they consider them fresher, of better quality, and with a unique taste (Starr et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2014). They see in this strategy new marketing opportunities as well as a mean to differentiate their business from other competitors, thus creating a competitive advantage (Namkung and Jang, 2017). However, the choice has been also motivated by the desire to support local economies (Frash et al., 2015), to provide an ethical and environmental footprint to the restaurant (Curtis and Cowee, 2009) and to offer customers an authentic experience based on ingredients and recipes related to the food and gastronomic heritage of specific areas (Kocaman, 2018; Home et al., 2020). Despite these premises, several studies have highlighted how logistical and time constraints (e.g., extra time to find local suppliers, producer’s ability to deliver on a regular schedule), low-quality consistency of the products, and an increase in supply costs may represent limits to the use of local traditional products and their purchase through alternative supply channels (Starr et al., 2003; Inwood et al., 2009; Sims, 2010; Roy et al., 2016).

While the global trajectory of this phenomenon has been discussed, the motivations and dynamics behind the revival of traditional food in the Global South need further exploration by expanding the debate from South America (Ginani et al., 2020) and Asia (Montefrio et al., 2020; Ozturk and Akoglu, 2020) in order to explore further in depth the emerging trajectories developing in contemporary Africa.

Even though previous studies conducted in Africa have highlighted the role restaurants can play in creating high-value market opportunities for smallholder producers (Mwema and Crewett, 2019) as well as in promoting and marketing the local food and traditional cuisine (Du Rand et al., 2003; Mnguni and Giampiccoli, 2019), little attention has been paid to the role that actors in the catering sector currently play in the revival and promotion of these resources.

Adopting a case study approach (Yin, 2017), the research addresses this topic by questioning the role of traditional foods and cuisine in the catering sector of Nakuru County, an emerging Kenyan agricultural and tourist hub, and investigates the main drivers behind their offering and demand. In seeking to better understand the adoption and diffusion of such products, we pay particular attention to the motivations that shape the decision of restaurateurs to include traditional foods and recipes in the culinary offering as well as to the perceived benefits and implications of this choice. To this end, we carried out a campaign of interviews with chefs, managers, and owners of a selected sample that included different restaurant typologies in terms of the type of menu offering, business structure, and potential target customers. Our study focused on documenting the traditional dishes and products offered in the selected restaurants, understanding the major trends in the industry regarding the attitudes of the different stakeholders toward traditional foods, and on exploring the organization of the supply chain for locally sourced traditional ingredients.

The specific objectives were to:

• define the role of traditional cuisine in the regional restaurant and catering sector.

• analyze the drivers that support the demand and supply of traditional dishes and ingredients.

• understand the organization of the restaurant supply chains for selected traditional ingredients.

• compare the main differences in the role of traditional food according to the type of restaurants and the public they address.

If in the current debate the rediscovery of tradition and the local is often read as a response to globalization (Belasco, 2008; Bessiere and Tibere, 2013; Kim and Iwashita, 2016), here we propose to look at the phenomenon via the adoption of an ethnographic lens (Marcus, 1998) and to explore the contingent problems of the foodscape as well as the material and immaterial elements that shape the use of local and traditional foods in the regional catering sector.

The article opens with an overview of the Kenyan agri-food sector, focusing on the recent trends linked to the rediscovery of traditional food and cuisine. After introducing the main socio-economic characteristics of the foodscape of Nakuru County, the article presents the findings of the fieldwork, showing the diversity of traditional products that compose gastronomic offerings of the regional catering industry and pointing out the motivations restaurateurs assign to their purchase and offerings. We therefore analyze two representative product categories of the foodscape and traditional gastronomy of Nakuru County, namely African leafy vegetables and indigenous chickens. Through the case studies, we argue that the return to local and traditional food is mostly linked to quality, safety, and traceability issues as well as to the emergence of more health-conscious eating habits, especially among Kenyan high- and middle-income customers.

Background

Kenya is one of the 10 largest countries and national economies in Africa and the main one of the East African Community (World Bank, 2020). It has seen fast and steady demographic growth since 2000, reaching 49.5 M people in 2016 (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Population Division, 2017). The national economy still relies heavily on agriculture, though the nation is facing fast urbanization, with an annual growth of 5% among the urban population and with 33% of the total population living in urban centers (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Population Division, 2017). The change in the national economy and the fast-growing urbanization have considerably shaped the agri-food sectors with an increasing industrialization and a focus on the production of cash crops for the global market, such as tea, coffee, tropical fruits, and horticultural products (Dolan, 2007).

In the face of this phenomenon, the origins of which lie in the colonial history of Kenya, there has been a progressive reduction in national agrobiodiversity (Maundu et al., 1999). The situation that emerged during the twentieth century has therefore shaped the dietary regimes and culinary practices of the living ethnic and indigenous groups that traditionally inhabited the Kenyan territory (Maundu and Imbumi, 2003). In this context, two main changes have arisen: on the one hand, there has been a standardization of the diet of the Kenyan population, driven by the adoption of staple foods (e.g., maize, wheat, rice, potatoes, cabbage, and kale) and dishes (e.g., cornmeal ugali, chapatti bread) that have become the common denominators of the national population’s diet (Raschke and Cheema, 2008); on the other hand, gastronomic contaminations have developed as a result of British domination and increased participation in global trade, with the introduction of exotic ingredients (Owuor and Olaimer-Anyara, 2007) and cooking techniques (Cusack, 2000) as well as with the internal migrations from rural areas to the main urban centers of the nation, which have led to a diversification of the urban foodscape (Mwangi, 2002).

While the fast urbanization of the Kenyan population has gone hand in hand with an increase in the consumption of international and processed foods (Maiyoh and Tuei, 2019), in recent decades there has been a growing demand for traditional products linked to the traditional food cultures of specific ethnic groups, such as camel milk and mursik (fermented milk), by the new middle classes that have migrated to urban areas (Musinga et al., 2008; Nduko et al., 2017).

It is possible to read within this framework the revival of specific vegetable species, including the so-called African leafy vegetables (hereinafter ALV), among Kenyan customers (Shackleton et al., 2009). While these vegetables have traditionally played a central role in the diet of several Kenyan ethnic groups, their consumption declined dramatically from pre-colonial times until the end of the twentieth century (Maundu, 1997). Nevertheless, since the second half of the 1990’s, partially as a result of campaigns and projects promoted by the Kenyan government, through the Ministries of Health and Agriculture, along with international organizations and NGOs (Ngugi et al., 2007; Gotor and Irungu, 2010), such products gained momentum and gradually shifted their status from “food for the poor” to premium products demanded by urban middle classes (Meldrum and Padulosi, 2017; Aworh, 2018). The increase in the consumption of ALV has also been linked to a renewed interest in the nutritional properties of these products and increasing consumer awareness about their health benefits (Gido et al., 2017; Neugart et al., 2017). In the urban areas, greater availability of ALV in supermarkets and shops has fostered the consumption of these vegetables (Abukutsa-Onyango et al., 2007).

A similar pattern marked the rescue of indigenous chicken breeds in Kenya, commonly known as kuku kienyeji. They are local poultry ecotypes of the species Gallus domesticus L., traditionally reared for meat production by small and medium producers in extensive systems and with limited use of external inputs (e.g., antibiotics, feed), relying instead on indigenous technical knowledge (Kingori et al., 2010). While the productivity of indigenous poultry is lower than exotic breeds, they are hardy, adapt well to the rural environments, survive on low inputs and adapt to fluctuations in available feed resources (Upton, 2000). For these reasons, the rearing of indigenous chicken is considered a poverty alleviation and food security strategy, especially in rural households. At the same time a growing market for the product has emerged in the last decades in both rural and urban areas driven by consumers’ preference for the characteristic leanness and flavor of indigenous chicken meat as well as the presumed organic nature of the product (Bett et al., 2012).

Looking at the Ho.Re.Ca sector (Hotellerie, Restaurant, Catering), changes in lifestyle and growing attention to health have contributed to shaping the industry, especially in urban areas. In major cities, there has been an emerging demand for healthier and natural products and the revival of indigenous foods (Adeka et al., 2009; Gakobo and Jere, 2016). While in the past the consumption of these products was limited to the domestic sphere and restaurants located in rural areas, nowadays several restaurants in urban settings offer dishes tied to the traditional food cultures of the new urban middle classes (Mwema and Crewett, 2019). It is therefore common nowadays to find in restaurants and hotels plant-based dishes made with ALV such as Solanum americanum L., Cleome gynandra L., Amaranthus sp., Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., and Brassica carinata A. Braun (Cernansky, 2015; Mwema and Crewett, 2019). Similarly, indigenous chickens have become commonly available ingredients in restaurants and hotels that serve convenience food both in urban and rural areas (Oloo et al., 2017).

It is within this socio-economic framework that the catering industry of Nakuru County should be understood.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Nakuru County, situated in the Rift Valley, covers an area of 7,235.3 km2 and is located between longitudes 35′ 28” and 35′ 36” and latitudes 0′ 12” and 1′ 10” South, lying about 2100 m above sea level. Nakuru borders eight other districts, namely Kericho and Bomet to the west, Koibatek and Laikipia to the north, Nyandarua to the east, Narok to the southwest and Kajiado and Kiambu to the south (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2010).

Nakuru is the fourth largest city in Kenya, hosting over 500,000 inhabitants with an economy heavily based on manufacturing and the service sector. The surrounding area, though, is known for its agriculture and is characterized by a wide network of small farms with an estimated average area per household of <1 hectare (Foeken, 2006). Farmers integrate cash crop production (e.g., potatoes, maize, and tomatoes) with the cultivation of traditional leafy vegetables such as Amaranthus sp., Basella alba L., Cleome gynandra, Solanum americanum, and Vigna unguiculata, mostly for the local market (Maundu, 1997; Maundu et al., 1999). Moreover, they usually supplement their income with livestock (shoats and cattle) and poultry rearing, especially indigenous chicken ecotypes (Kyule et al., 2014).

Nakuru is a cosmopolitan region with an ethnoscape dominated by Kikuyu and Maasai communities originating from the region along with other ethnic groups (i.e., Kalenjin, Luhya, Luo, and Kamba). The multicultural milieu is the result of the internal migrations that moved people from all across Kenya to look for employment in the service industry of Nakuru town as well as in the agricultural sector, especially in the flower farms around Lake Naivasha (Sassi and Zucchini, 2018).

The growing urbanization and the multi-ethnic dimension of Nakuru County, along with the rise of the tourism industry, have promoted in the past decades a significant transformation of the agricultural and gastronomic sectors in the area. In this context, there has been an increasing demand for traditional foods from the new urban middle classes, especially for traditional leafy vegetables (Knaepen, 2018). Little attention, however, has been paid so far to the impact of this phenomenon on the regional catering sector.

Fieldwork Activities and Sample Design

Building on previous studies carried out in Nakuru County (Barstow and Zocchi, 2018; Fontefrancesco et al., 2020), this research aimed to explore the drivers behind the offering of and demand for traditional products, paying particular attention to the dynamics of the regional catering and hospitality sectors.

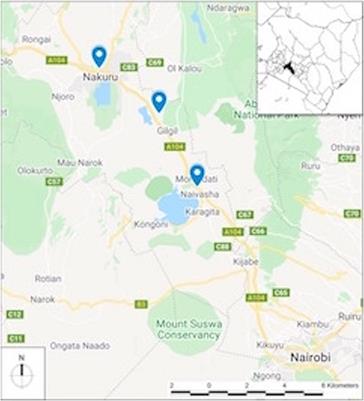

Fieldwork research was conducted between August 2019 and January 2020 in Nakuru County as part of the broader research project “Sistemi Alimentari per lo Sviluppo Sostenibili” funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research. It analyzed ethnographically 41 restaurants and hotels located in the city of Nakuru and tourist areas near Lake Elementaita and Lake Naivasha (Figure 1).

Restaurants were selected through a mix of convenience and purposive sampling to be representative of the regional catering sector according to the type of menu offerings, the location of the restaurant, and the potential target customers.

The selection of the restaurants entailed three main stages:

I A general mapping of restaurants and hotels in the three key locations, analysis of the culinary offering, and definition of the potential target audience, when possible, through the analysis of the restaurants’ web pages.

II Classification of restaurants according to the type of offering and potential target clientele. Based on the findings of the first stage of the preliminary research, we defined three classification categories as follows: (1) restaurants that serve Kenyan cuisine mostly to local low-income customers; (2) restaurants that serve Kenyan and international cuisine mostly to middle- and high-income national customers, and (3) restaurants that serve Kenyan and international cuisine mostly to national tourists and international customers.

III A preliminary visit to the restaurants and/or the organization of interviews with the owner, manager, or chef. This activity was carried out in the periods prior to the fieldwork activities in collaboration with Slow Food Kenya.

To this end, we carried out a preliminary mapping with Slow Food Kenya using a combination of tools and data repositories. Restaurants were selected by means of an Internet search supplemented by local knowledge. On the one hand, we conducted online research using Google maps and web platforms specialized in the booking and review of catering and hospitality activities including TripAdvisor, Booking.com and EatOut. On the other hand, we conducted exploratory fieldwork to map restaurants aimed at a local clientele, which did not have web pages. This operation was done with the help of local assistant researchers with extensive knowledge of the regional gastronomic sector. Based on the information collected through the two mapping methods, we completed a list of 75 restaurants. Through the analysis of the web pages and the information gathered during the exploratory fieldwork, we were able to define in general terms the culinary offerings of the restaurants, understand the presence and relevance of traditional Kenyan dishes, and identify the potential customer targets. Drawing from this information, we delineated three macro-categories of restaurants, taking the following variables into consideration: consumer provenance (local, national, and international), spending capacity of the potential customer (low-income, middle-/high-income), culinary offering with respect to the presence of Kenyan dishes (most of the food served is based on Kenyan cuisine, about half of the menu is based on Kenyan cuisine, just a few dishes from Kenyan cuisine). Subsequently, we contacted the restaurants to explain the aims of the research and to organize the interview. Of the 75 restaurants, 41 agreed to take part in the research. The research was limited with respect to the views of the participants who agreed to participate in the study within the scope of sampling and the time they spared for the study.

Data Collection

Data collection was done through face-to-face structured and unstructured interviews with 51 professionals, including six restaurant owners (four women and two men), 29 food and beverage managers (12 women and 17 men), and 16 chefs (four women and 12 men). All of the informants were key decision makers in designing the menu and/or in sourcing food for each restaurant.

The interviews investigated the presence of traditional foods and dishes in the restaurants’ culinary offerings and the dynamics driving the offering of and demand for such products. We paid great attention to the motivations behind the inclusion of traditional foods on the menus, the selection of supply chains for local traditional ingredients, and the perceived benefits linked to these choices. During the interviews, we asked informants to present the main characteristics of the restaurant (e.g., type of cuisine, customers’ profile, etc.), to list the most important traditional dishes offered on the menu, and to describe the ingredients and cooking methods used for their preparation. In addition, we explored the main reasons why informants included traditional dishes in the restaurant’s culinary offerings. Subsequently, we investigated the organization of the supply chain for locally sourced traditional ingredients, paying particular attention to the places and means of supply, the criteria to choose specific supply channels, and the relative advantages the informants attached to this choice. Eventually, we asked the informants to discuss the major trends in the industry regarding the attitudes of the different stakeholders toward traditional foods and cuisine.

The research also included visits to the kitchens and dining rooms to examine the ways of preparing, presenting, and communicating traditional dishes. Moreover, copies of the written menus were obtained when available and pictures of the dishes were taken with the permission of the interviewees. Interviews were conducted in English by the researchers and in Swahili by the research assistant fluent in Swahili and English; they lasted ~45 min. each. Prior to each interview, informed consent was obtained, as recommended by the code of ethics of the American Anthropological Association, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Gastronomic Sciences (AAA., 1998). Interviewees were informed in advance about the rationale, aims, methods, and expected outputs of the project.

The Characteristics of the Sample: Customers, Location, Culinary Offerings, and Services

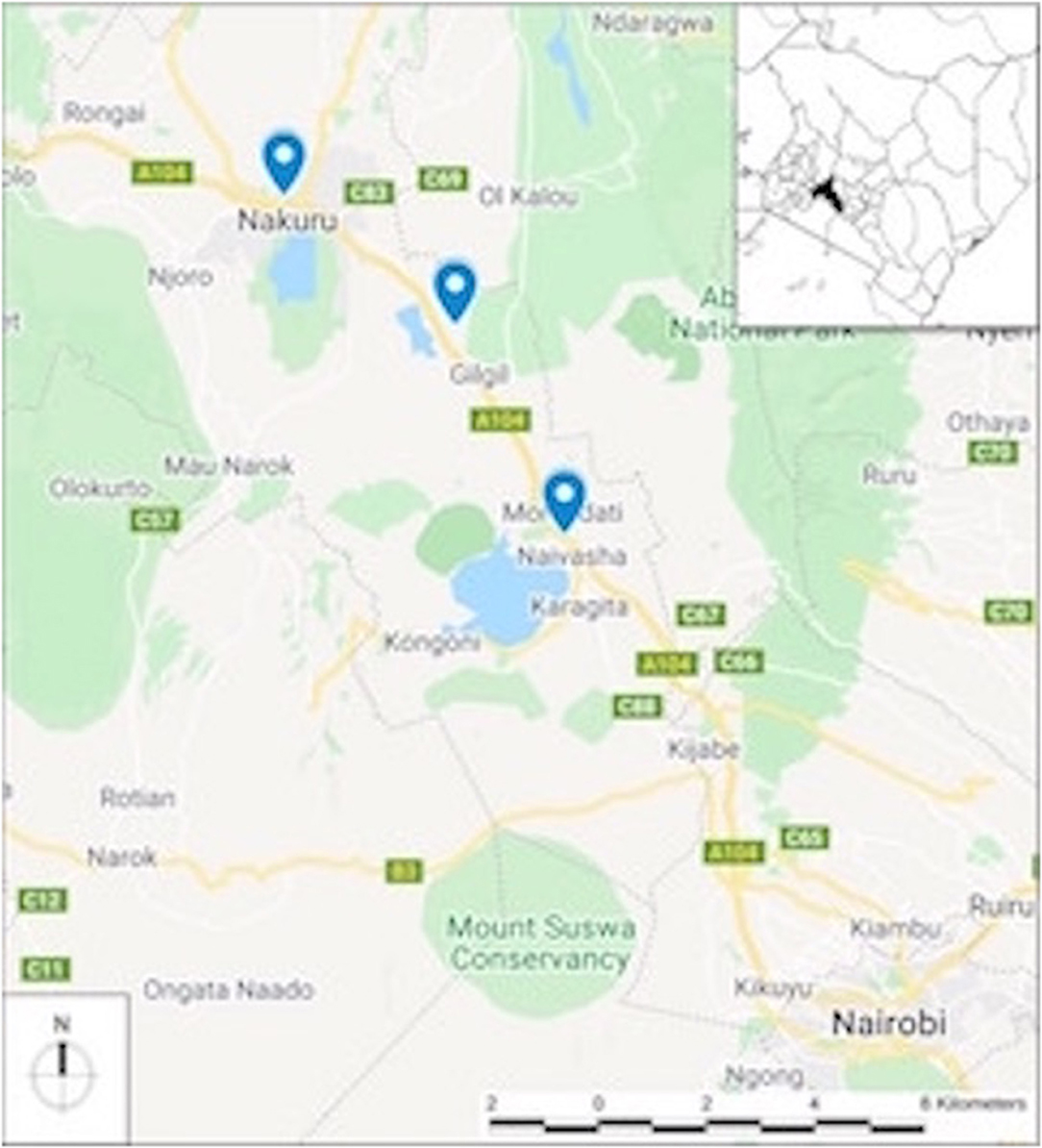

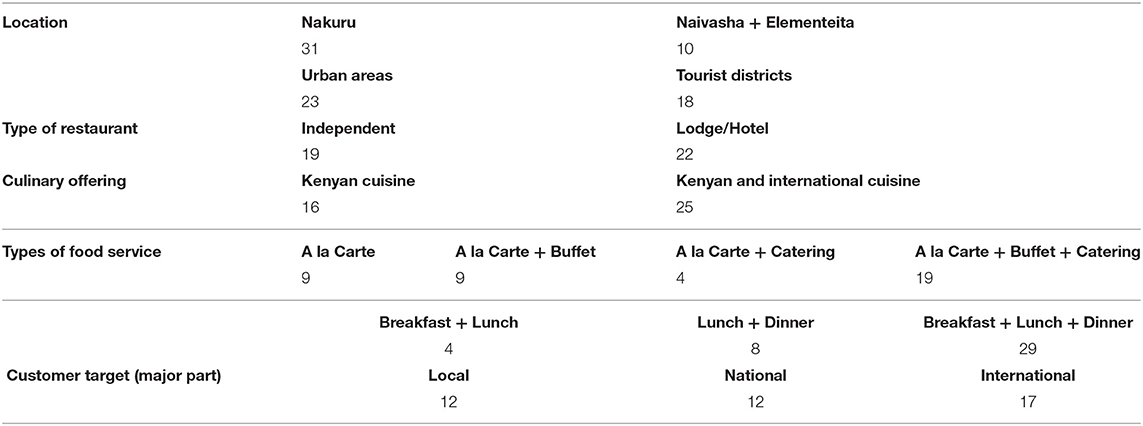

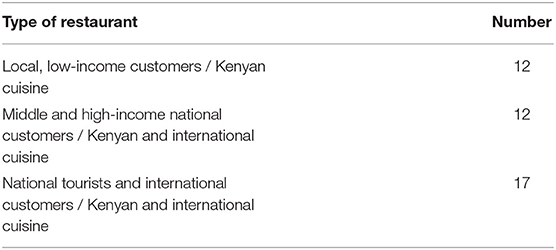

Tables 1, 2 summarize the main characteristics of the surveyed restaurants.

Of the 41 restaurants included in the sample, 23 facilities were located in urban areas, most of them in Nakuru town, and 18 restaurants in tourist districts, especially near Lake Elementeita, Naivasha, and around Nakuru National Park. Nineteen restaurants were independent and 22 were part of hotels and lodges. Concerning the type of cuisine, 16 restaurants offered mainly Kenyan dishes, and 25 restaurants also included international recipes on their menus (e.g., Italian, Indian, and Chinese). The majority of the restaurants surveyed (n = 29) restaurants offered breakfast, lunch and dinner services. Moreover, about 75% of the sample integrated à la carte menus with buffets and private catering, mainly for weddings and seminars.

Based on the preliminary analysis and the interviews, it has been possible to categorize the restaurants according to the type of offerings and the public they target. The sample includes 12 restaurants that served Kenyan cuisine mostly to local low-income customers, 12 restaurants that served Kenyan and international cuisine mostly to middle- and high-income national customers, and 17 restaurants that served Kenyan and international cuisine mostly to national and international tourists.

Data Analysis

The study was largely based on a qualitative analysis of the interviews conducted with professionals in the regional catering industry. The interviews and the filed notes were transcribed, entered into NVivo qualitative data analysis version 12.5.0 (QSR International, 2019), and codes, concepts, and nodes were generated during the analysis.

For data analysis, a descriptive analysis method was used. On the one hand, we selected and organized the data for the 51 interviews and menus in an Excel database. Afterwards, we carried out an analysis to estimate the diversity and frequency of the traditional dishes and ingredients reported during the interviews. For the definition of “traditional food” and “traditional dishes,” we took into account the perception of the informants. The frequency was instead calculated based on the number of mentions by the interviewees and cross-checked, when possible, with the menus and the webpages of the restaurants. On the other hand, data were analyzed using a quality content analysis (Elo et al., 2014), with the aim of exploring the motivations interviewees attached to the inclusion of traditional food and recipes in the offerings of the restaurants as well as of identifying the main drivers and consequences behind the revival of traditional cuisine. To this end, the interview transcripts were systematically coded and triangulated with the filed notes, the menus, and the other collected during the fieldwork. Themes and subthemes were identified relating to the role of traditional foods in the selected restaurants, the attributes restaurateurs attached to them, as well as the criteria underpinning the choice of the procurement systems for locally sourced traditional ingredients.

Results

The Diversity of Traditional Dishes and Ingredients in the Regional Restaurants

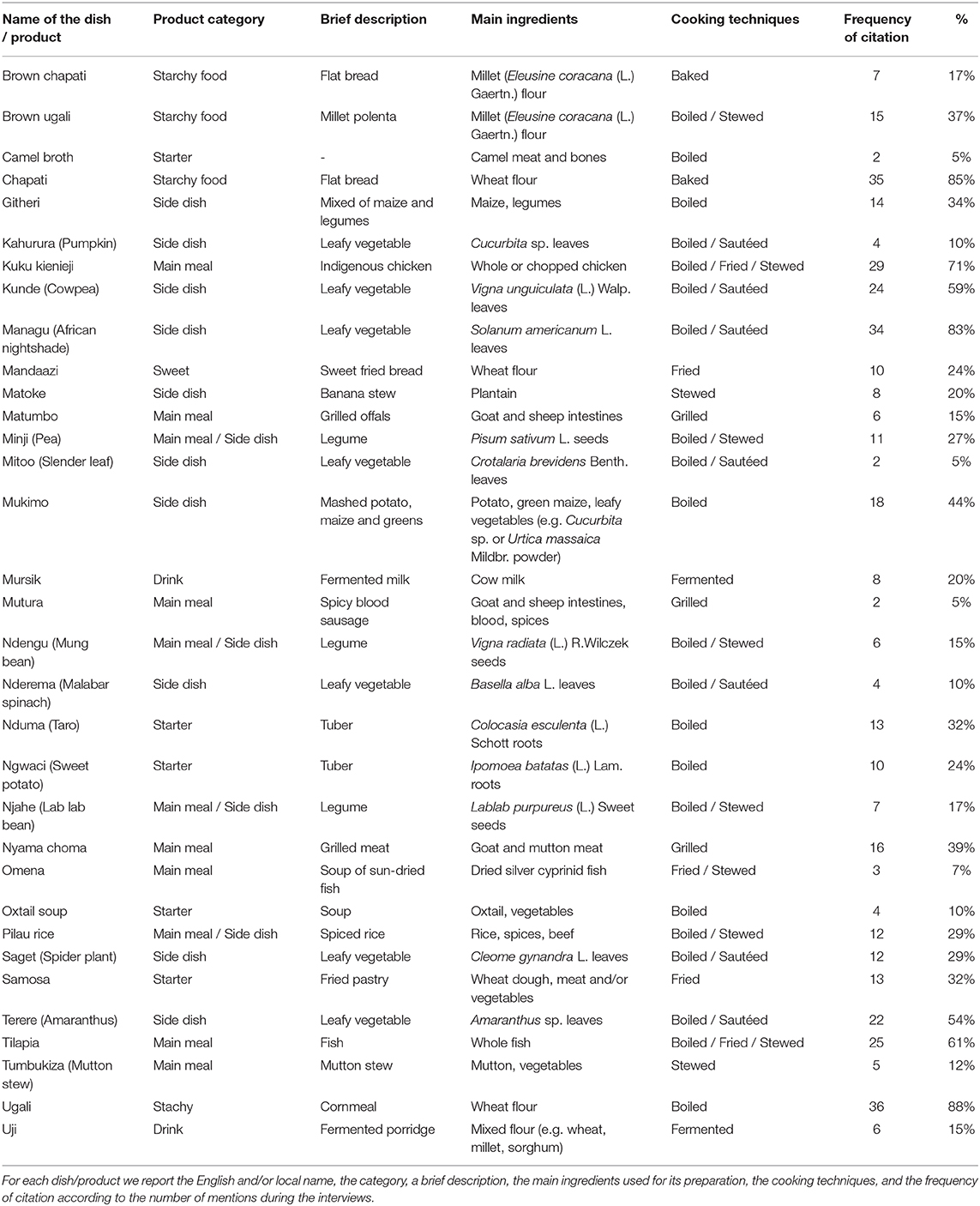

During the interviews and restaurant visits, 33 recipes and ingredients that informants defined as traditional (i.e., representative of the Kenyan culinary traditions) were reported. Table 3 summarizes the most representative dishes documented during the interviews and gives their names (in English and/or in the local language), category, a brief description, the main ingredients used for their preparation, the cooking techniques, the frequency of citation according to the number of mentions by the interviewees and its relevance in percentage.

Table 3. List of the most representative Kenyan traditional dishes and ingredients documented during the fieldwork.

Respondents defined the “traditionality” of the dishes mostly based on the type of ingredients and the cooking techniques used for their preparation. In this sense, as shown through the analysis, informants associated products such as leafy vegetables (number of mentions = 120) and white meat (number of mentions = 29) and cooking methods such as boiling and/or stewing (number of mentions = 149) with traditional Kenyan cuisine. Moreover, the analysis highlighted that about 65% of the dishes mentioned by the respondents were vegetarian, whose ingredients include tubers, cereal flours, and leafy vegetables.

As reported in Table 3, starchy foods such as ugali (cornmeal), chapati (flat bread), and tubers (e.g., nduma (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott), ngwaci (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) were the most common items in the culinary offerings of the restaurants. Similarly, ALV, especially managu (Solanum americanum, n = 34), terere (Amaranthus sp., n = 22), kunde (Vigna unguiculata, n = 24), saget (Cleome gynandra, n = 12), kahurura (Cucurbita sp. n = 4), and ndrema (Basella alba, n = 4), played a central role in the culinary offerings both from a quantitative point of view and in terms of diversity of species offered by each restaurant on their menus. Overall, eight different species of ALV have been documented during the fieldwork, and about 80% of the surveyed restaurants included at least one of them in their culinary offerings. While these vegetables are mostly boiled or sautéed and served as side dishes, they are also some of the ingredients representative of local dishes such as mukimo, a mixture of mashed potatoes, green maize, and leafy vegetables such as Cucurbita sp. and Urtica massaica Mildbr. leaves. On the other hand, restaurants offered a more limited range of meat dishes, with the most frequently mentioned being kuku kienieji (boiled or stewed), tilapia (deep-fried or stewed with vegetables), and nyama choma (grilled mutton and goat meat), the latter usually prepared on request.

The Role and Diversity of Traditional Kenyan Dishes in the Culinary Offerings: Exploring the Motivations of the Restaurateurs

Despite all the restaurants in the sample offering some dishes considered “traditional” by the interviewees, some differences in the role of Kenyan cuisine emerged, with the differentiation mostly linked to the customer profiles and the location of the restaurant.

The restaurants located in touristic areas presented a more diversified culinary offering, including recipes from international and Western cuisine. In this context, the offering of traditional Kenyan dishes covered a marginal portion of the whole offering, being mostly limited to buffets and to a small number of items such as starchy foods (e.g., ugali, chapati) and leafy vegetables, especially managu (Solanum americanum) and terere (Amaranthus sp.). This trend was even more evident in cases when the restaurant was part of hotel and lodge facilities that target mostly international customers. Interviewees justified the choice of having a broader menu rather than focusing on a specific culinary offering as an essential strategy to meet the demands of the widest possible spectrum of customers.

As stated during an interview with a restaurant manager of a starred hotel near the shores of Lake Elementeita,

“In recent years, the number of foreign customers and domestic guests from Nairobi has increased. If we want to be competitive on the market, we must have a rich and varied offering to satisfy the needs of our guests. In our menu, we have a selection of local and international cuisines, such as Italian, Indian, and Chinese. We cannot include a broad variety for each type of cuisine. Nevertheless, we try to meet the needs of our guests by offering dishes that are not on the menu in the buffet. We have a few Kenyan dishes on our menu, though we offer them on the buffet or during special events. More and more national and international customers are asking for traditional dishes. However, there is still a great portion of our guests who want to eat international dishes during their stay.”

Differently, in the restaurants targeting mainly national Kenyan customers (i.e., urban middle- and high-income patrons and tourists), traditional Kenyan cuisine represented the main pillar of the culinary offerings in terms of the diversity of the dishes, the ingredients used for their preparation, as well as in the ways of presenting and communicating them on the menus. The majority of restaurants of this kind had on their menus whole sections dedicated to traditional Kenyan cuisine, including starters (e.g., taro and sweet potato), main dishes (e.g., indigenous chicken, tilapia), starchy foods (e.g., mukimo, githeri, brown chapati, brown ugali), and side vegetables made with managu (Solanum americanum), terere (Amaranthus sp.), kunde (Vigna unguiculata), saget (Cleome gynandra), kahurura (Cucurbita sp.), and ndrema (Basella alba), all of them ALV. The diversity of the Kenyan dishes further increased as restaurateurs offered on request some products that were not on the menu, such as mursik (traditional fermented milk) and nyama choma (grilled goat and sheep meat), especially for seminars and other private events.

As highlighted during the analysis of the restaurant menus, a few restaurants (about 10% of the sample) further highlighted the centrality of the Kenyan cuisine on their menus by including information on the history of the dishes, their connection to the culinary traditions of specific regions and ethnic groups, and the origin of the ingredients used for their preparation. This communication strategy was limited to a restricted group of restaurants located in Nakuru town whose main targets are national and international high-income customers. As reported in the following examples, it entailed mainly the presentation of animal-based dishes.

• Kuku kienyeji: the road runner chicken is aptly known as ingokho. Back in the days in Western Kenya, the Ingokho was served on special occasions and the chimondo (gizzards) was reserved for the special guests. Traditionally cooked in a stew to delight the palate.

• Tumbukiza literally means submerge. It is a dish originating from the rich culture of Central Kenya. It is the art of mixing and cooking everything together in one pot.

Moreover, the research highlighted that the name of the dishes and/or their descriptions comprised adjectives such as “traditional” and “natural” as a way to clearly communicate the cooking techniques, their ingredients and their production methods. The triangulation of the data further stressed the relationship between the terms “traditional” (n = 14) and “natural” (n = 11) and the culinary preparations that have indigenous chicken meat and ALV as main ingredients.

As reported during the interviews, the informants frequently associated traditional and natural foods to specific production systems that rely on the minimal use of external inputs and technologies. The majority of the interviewees defined indigenous products and traditional dishes as opposed to exotic species and industrial, junk food. According to their knowledge and to what they have learned from media communication, such products are associated with the spread of disease such as cancer since they are often cultivated with a great quantities pesticides, as in the case of exotic leafy vegetables like kale, or reared with the use of antibiotics and hormones in the case of broiler chickens. As one food and beverage manager who worked for several years in Nairobi explained,

“Due to the increasing spread of health-related diseases, many Kenyan urban customers have gradually changed their eating habits by reintroducing in their diet healthy and natural foods, often those foods their parents used to produce and cook.”

Our informants often linked the growing interest in traditional foods and the increasing attention toward Kenyan cuisine in the Nakuru catering sector as a consequence of the socio-economic and demographic changes that have marked the region over the last decade. Following the economic boom in the region, an increasing number of Kenyan customers, especially from Nairobi, have been visiting the region both for leisure and business reasons.

As stated by the food and beverage manager of a lodge near Nakuru town,

“We are experiencing a significant increase in Kenyan customers. They are businessmen and tourists belonging to the middle class of Nairobi. During their stay, they want to eat traditional dishes prepared with natural ingredients. In recent years these clients have been paying more attention to their diet. For instance, they prefer to eat traditional vegetables and white meat instead of red meat and fried potatoes. This is something that has spread recently as a consequence of some food scandals. People are paying more attention now to what they eat, as they are more concerned with diseases such as cancer and obesity. If we want to keep these customers, we need to assure them that the food we cook is nutritious and safe for their health.”

Similarly, the head chef of an independent restaurant located in the urban center of Nakuru highlighted this trend, pointing out the changes in the eating habits of the customers:

“If until recently our customers ordered broiler chicken, cabbage and sukuma wiki, they are now asking for traditional products such as kuku kienyeji, managu, terere, and kunde, cooked with a limited amount of fat and without the addition of spices (i.e., flavor enhancers). They want simple dishes made with traditional products and cooked as their mothers did at home. They perceive these dishes as healthier and safer. For instance, people prefer kuku kienyeji rather than broilers, as its meat is tastier. Customers are aware that farmers raise the animals and open-air feed them with natural products. Broilers, instead, eat only grains and are treated with antibiotics.”

The excerpts from the interviews show how the revival of traditional cuisine is mostly linked to the search for natural and traditional products by the urban middle and high-income classes as a way to improve their health and well-being. To meet this growing demand, restaurateurs offer traditional ingredients, such as ALV and indigenous chickens that their customers perceive as safer, fresher, and more nutritious. Moreover, about 30% of the informants justified the choice of offering indigenous chicken meat to meet the taste preferences of the national customers who prefer the sensory qualities and texture of this meat to those of commercial broiler chickens (i.e., improved poultry breeds reared in intensive systems).

Although the restaurant addressing local low-income customers also based their culinary offerings on traditional Kenyan cuisine, the diversity of dishes and ingredients was lower compared to the other restaurant categories. During the interviews, the restaurateurs highlighted an interesting factor behind the choice of dishes to include in their culinary offerings; the ethnic profile of the customers was the main driver behind the design of the menus. Following the migratory flows from rural areas to Nakuru town, demand for products linked to ethnic gastronomic traditions of migrants emerged, thus fostering the rise of a new niche in the catering industry. As pointed out by different owners and chefs, many of their customers are economic migrants, especially men, who order dishes they cannot eat any more at home due to the limited time available, the difficulties in finding the ingredients, and the lack of knowledge on how to cook them.

In this context, therefore, one can explain the rise of restaurants specializing in fish-based dishes, such as omena (small dried fish) and tilapia, millet ugali, and leafy vegetables such as mitoo (Crotalaria brevidens), linked to the gastronomic culture of the Luo and Luhya people, and mursik, a fermented drink made from milk and tied to the food culture of Kalenjin.

This circumstance is well-exemplified by what the Luo women who own a restaurant in the city center of Nakuru have witnessed,

“I moved to Nakuru from Kisumu over 20 years ago. I initially ran a small kiosk where I sold fish coming from my hometown. Over time I realized that several of my customers, most of them Luo, were looking for a place where they could eat traditional dishes such as omena soup and millet ugali. So I decided to start a restaurant business and offer my customers traditional Luo dishes, the ones I learned from my mother. Now, I am running the business with my daughter. We have an affordable menu with a few dishes, most of them based on fresh and dried fish. We also offer traditional leafy vegetables such as mitoo and mlenda. We also provide a delivery service to the offices and workers in the neighborhood.”

The Relationship Between “Traditional” and “Local”: an Analysis of Restaurant Supply Choices for ALV and Kuku Kienieji

The inclusion of traditional products in the culinary offerings partially shapes the organization of the food procurement system and the criteria underlying the choice of specific market channels. Several restaurateurs agreed that the growing demand for traditional foods often entails a reorganization of the food supply chain to guarantee customers safer and fresher ingredients.

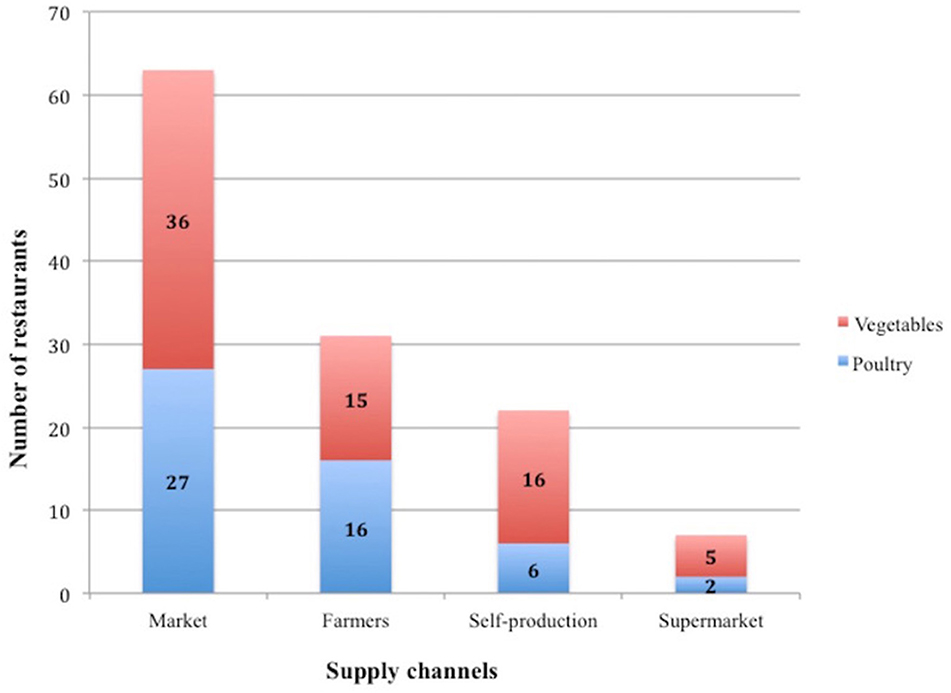

While wholesale and retail markets are still the main supply channel, about 65% of the surveyed restaurants have recently integrated their food procurement systems by using alternative channels, such as purchasing products directly from local producers (n = 22) and self-production for the supply of those products (n = 31), with this practice being more common among restaurants targeting middle- and high-income Kenyan customers and national tourists (Figure 2).

In this context, two products are particularly helpful in understanding the consequences of the rising demand for traditional foods on the organization of restaurant activity and the food procurement system: ALV and kuku kienyeji. As we observed during the fieldwork, these products are among the most used ingredients in the majority of the surveyed restaurants, unlike other products such as camel-based and fish-based dishes (e.g., omena soup), whose offering is still restricted to a small segment of the regional catering industry (i.e., the restaurants target local clientele).

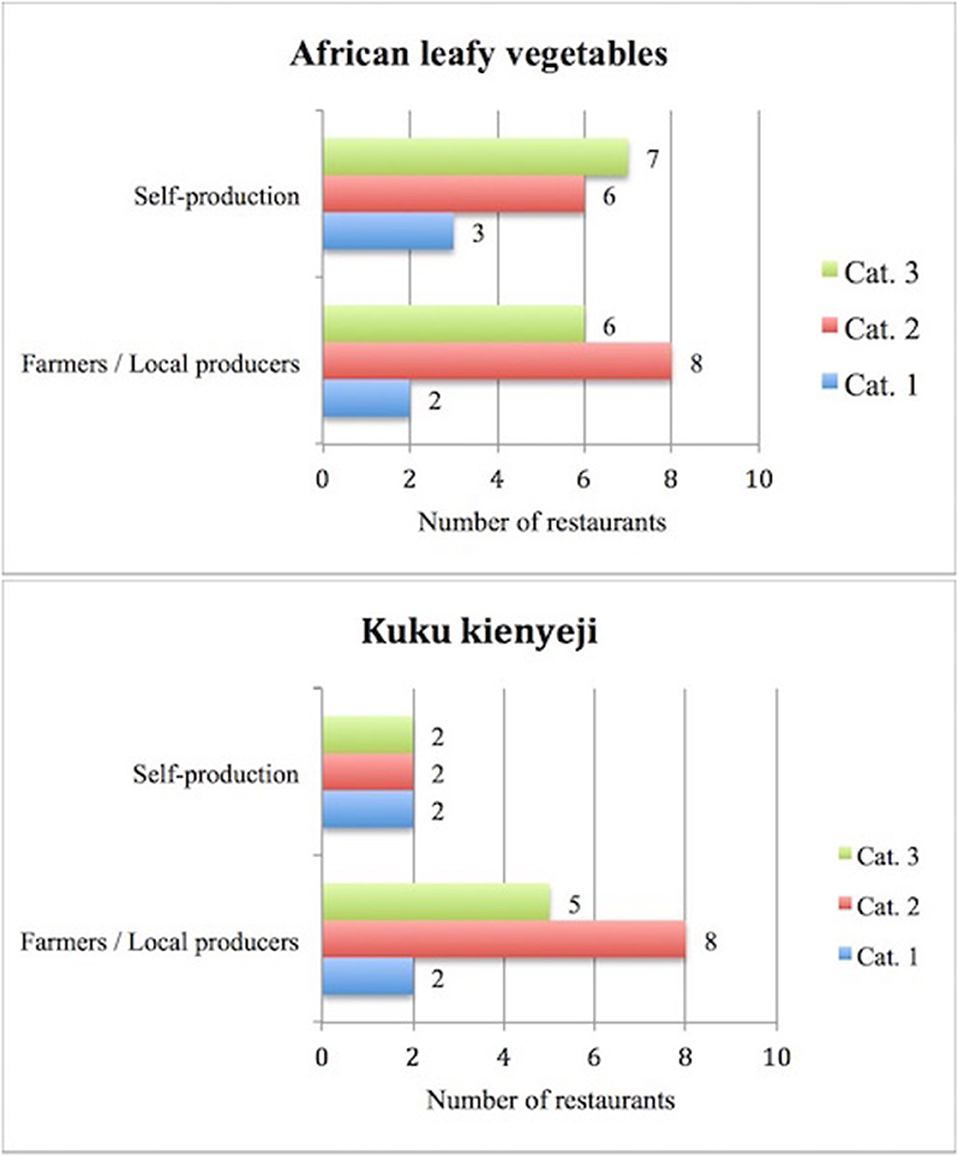

Regarding the supply of indigenous chickens, 40% of restaurateurs stated that they purchased this product directly from local producers. From a quantitative point of view, this practices was more common in restaurants that serve middle and high-income national customers (n = 8) and national and international tourists (n = 5). A small number of restaurants (n = 6) reared their own chicken due to the spatial and temporal constraints connected to this activity.

The restaurateurs recognized the overall economic benefits (i.e., price stability and bargaining power) of these practices as well as the role they play in guaranteeing the consistency of supply both from a quantitative and qualitative perspective.

As the owner of a restaurant in Nakuru renowned for offering indigenous chicken told us,

“When I started my business, I used to purchase most of the chickens from markets in town, but I had several issues with vendors. They often failed in supplying the produce, the price varied considerably from one day to another, and the quality of the meat was very poor. I therefore decided to go directly to producers in the area. Now, I buy a stock of chickens from local breeders in the County and I keep them on a farm near the restaurant. I slaughter the chickens at the municipal slaughterhouse according to the number of orders I receive at the restaurant. In this way, I can offer my customers a high-quality product that is tastier, safer, and at a fixed price, even when demand is very high.”

If dealing directly with the producers allows the costs of the supply to be reduced, given the shortening of the value chain, most of the interviewees stressed the importance of knowing the places and methods of production as a fundamental element in the relationship with end customers who are increasingly concerned about their health and who pay more attention to the quality, safety, and origin of the food they eat. According to most informants, the reduction in the intermediary steps in the supply chain was perceived as a suitable strategy to have better control over the traceability of the product, more reliable information on the production methods, and in so doing, to offer customers a high-quality and safe meal.

As far as the supply of ALV is concerned, the decision is to reduce intermediary steps by buying directly from local producers or, more frequently, by self-production with both of these practices being more commonly adopted by restaurants that serve middle- and high-income national customers and national and international tourists (Figure 3). Differently from what observed for indigenous chicken supply, self-production was more common than direct purchase from local producers. While the majority of the informants agreed on the economic benefits of this practice, they also pointed out several barriers, including reliability of the suppliers, quality consistency of the products, and logistical issues since on most of the occasions someone from the restaurant staff has to pick up products from the farmers’ place.

Figure 3. Alternative supply channels for ALV and kuku kienyeji according to the restaurant categories.

Although in a limited number of restaurants surveyed was able to cover more than 40% of the total supply, this channel covered an important economic function for restaurateurs, it also contributed to an improvement in the quality standard of the culinary offering (i.e., fresher products), and it guaranteed better the traceability of the products, food safety and overall quality of the dishes offered at the restaurant.

As reported by a manager of a tourist lodge located near Lake Nakuru,

“Market vendors can hardly guarantee the traceability of the products they sell. I cannot offer products that I do not know where they come from and how they were cultivated. If a customer found out that I sold him/her products grown with chemicals, the image of my restaurant would suffer from it. For this reason, two years ago we started our garden. We have a small piece of land of about 2 acres. We are planning to expand the project and to achieve self-sufficiency at least for managu and terere.”

At the same time, self-production, mostly of managu, terere, and kunde, played a crucial role in guaranteeing the consistency of the produce, as it allows some of the main problems connected to the supply of ALV to be overcome, such as the lack of refrigeration systems, the high perishability of these ingredients, and the fluctuation in prices, especially during the dry season.

Overall, the analysis showed that freshness of the ingredients, traceability and price were the main benefits perceived by the restaurateurs who produce directly a portion of the vegetables in restaurant gardens.

While restaurateurs that run catering business that serve local clientele reported an interest in purchasing products directly from producers and/or producing a portion of these ingredients in restaurant gardens and farms, they highlighted the economic, temporal and logistical constraints connected to this opportunity and, therefore, the necessity to rely on the market (retail and wholesale). In particular, informants stated that the choice to buy from local markets was motivated by the need to access fresher ingredients and cope with the logistical and technical barriers such as the lack of adequate preservation systems and places to store the ingredients. This strategy, however, makes the restaurateurs more exposed to the price fluctuations of products in the local food market.

Discussion

The Role of Traditional Products in the Catering Sector

As already shown in other areas of Kenya (Gakobo and Jere, 2016; Mwema and Crewett, 2019), our study highlights that the rediscovery of traditional foods is an incipient trait of the foodscape of Nakuru County. This trend is, in turn, reflected in the catering industry and offers interesting perspectives on the role of restaurants in the promotion of Kenyan food and gastronomic heritage.

Even though in restaurants aimed at an international clientele Kenyan cuisine, still holds a marginal position and the consumption of ethnic products, such as omena and mursik, is limited to a small portion of local patrons, the research has shown a growing and diversified offering of local products and traditional foods in facilities aimed at middle- and high-income Kenyan customers and tourists. Restaurateurs justify this as being a result of the development of national tourism from urban areas and the attention these customers pay to diet and health.

Overall, it has been possible to identify the socio-economic changes that have occurred in recent decades as one of the main reasons for the introduction of traditional products and recipes in regional restaurants. On the one hand, as already highlighted by Mwangi (2002) in his study on street food restaurants in Nairobi, the emergence of a supply for traditional food is linked to the increasing migrations from urban areas of the County and the consequent development of demand for product tied to the food cultures of specific ethnic groups. On the other hand, our informants justify the rising demand for traditional food as a consequence of the increasing presence of national customers from urban areas, such as Nairobi, who visit the region both for leisure and business purposes. Our findings are in line with the works conducted in France by Bessiere and Tibere (2013) and the study of Du Rand et al. (2003) in South Africa that highlight the connection between the rise of tourism and the incipient promotion of local and traditional elements of the food and agricultural heritage; however, some differences emerged in the specific drivers behind this phenomenon in the study area.

The Drivers of the Traditional Food Revival

The research highlighted that the revival of local and traditional ingredients, especially ALV and indigenous chickens, has been driven by heterogeneous and interconnected drivers that entail both the nutritional and sensorial properties of the products as well as elements connected to the economic and logistical specificities of the restaurant business.

In the case of ALV, the interviewees highlighted the awareness of customers concerning the nutritional benefits of this indigenous species compared to exotic vegetables such as spinach and kale, as an important element in the shaping of the culinary offerings of the catering industry. Specifically, they pointed to increasing attention to health and diet on the part of the urban population, especially from middle- and high-income customers, as one of the main drivers behind their diffusion. Changes in the lifestyle and greater attention to health among the middle and high-income urban dwellers have been documented as some of the main reasons behind the consumption of ALV at the domestic level (Ngugi et al., 2007; Gido et al., 2017). These changes, in turn, can be linked to specific campaigns carried out by the government and international organization. For instance, Biodiversity International in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture and KARI (Kenya Agricultural Research Institute) carried out a campaign aimed at preserving the biodiversity of ALV, its production, and consumption through the creation of commercial chains between rural-urban areas and the development of awareness campaigns to promote the nutritional benefits of these vegetables. As already assessed (Gotor and Irungu, 2010), these activities along with the broader changes in lifestyle have shaped the dietary habits of middle- and high-income customers, especially in cities such as Nairobi. Our study highlights that these changes are also shaping the eating behaviors of the urban population outside the domestic sphere. Similarly, as already noted by Bett et al. (2012), the preference for kuku kienyeji is tied to the perceived healthiness of this product as well as to its organoleptic qualities. Overall, this attitude reflects a growing concern about non-communicable food diseases, in particular, cancer (Maiyoh and Tuei, 2019), linked to the consumption of processed products and the use of chemicals and antibiotics in agriculture and chicken rearing.

The connection between the rise in the consumption of traditional foods and changes in the food habits toward healthier and safer diets marked the first stage of development of the revival of local and traditional food in other geographical contexts such as in North America (Ilbery et al., 2005; Inwood et al., 2009) and Europe (Murdoch et al., 2000). This trend seems to guide the rediscovery of indigenous and traditional food in the Nakuru region too. In this context “traditional” is equated with “healthy.”

The Specificities of the Traditional Food Revival

The rediscovery of ALV and indigenous chicken implies, in turn, an incipient localization of the food supply chains. While the market is still the main channel for the purchase of raw materials for local restaurants, thus discounting the limits of poor traceability, food safety, and price fluctuations, restaurateurs have begun to respond to customers’ needs by developing alternative production chains based on self-production or direct commercial relationships with local small-scale producers.

In the case of ALV, these strategies give greater control to the restaurateurs with respect to the traceability of the products, as the restaurateur can periodically check the quantity and quality of the production. Moreover, considering the perishability of the leafy vegetables, restaurateurs justify the choice both as a solution to offering fresher products, compared to those found on the market, and in economic terms to coping with price fluctuations and uncertain availability of these products on the market. Similarly, for the production of kuku kienyeji, the disintermediation of the market through self-production or commercial agreements directly with producers offers greater control over the product and production methods, thereby guaranteeing traceability and safety. The results are consistent with study findings in the hospitality and tourism setting (Starr et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2014; Ozturk and Akoglu, 2020) that point to the quality and freshness of traditional, artisanal, and local products as key drivers behind the localization of the food supply chain. However, our findings differ in regards to the economic and logistical constraints that for several scholars inhibit the development of alternative supply systems, including direct commercial relationships with local producers. In their study Inwood et al. (2009) pointed out that convenience and ease of access represents a limit to the development of direct marketing relationships between restaurants and farmers. Starr et al. (2003), in their analysis of the restaurant sector in Colorado, found that, despite the interest in purchasing locally grown foods, logistics, reliability, and consistency of the supply were raised by the restaurateurs as the main barriers. Similarly, Murphy and Smith (2009) observed that coordination with different local farmers might increase delivery times and result in higher costs for the restaurant. Contrary to what has been assumed in these studies and other works that addressed this topic (Sharma et al., 2009; Roy et al., 2016), our findings demonstrated that these strategies do not bring about an overall increase in costs, but they reduce the exposure of restaurants to price fluctuations of the market; thus, they have a positive impact on the restaurant business. This trend represents one of the central elements of the emergent gastronomic phenomenon.

In previous studies, the localization of the supply chain has been associated with an attempt to promote more sustainable and inclusive gastronomic practices by creating alliances with local producers and connecting the restaurants with other local stakeholders (Martinez et al., 2010; Lane, 2011), improving the food procurement system through environmentally responsible procurement practices (Curtis and Cowee, 2009) and enhancing the local food heritage and its associated biodiversity (Fusté-Forné, 2019). Our study highlights that the ethical and environmental elements, as well as the willingness to boost the local economy, still play a marginal role in this phenomenon since attention to freshness, traceability and quality consistency prevails.

In the context of high market fragmentation (Fontefrancesco et al., 2020) and difficult traceability of food supplies (Chemeltorit et al., 2018), traditional foods and their purchase through alternative supply chains are therefore a potential answer to the search for healthy, fresh, and safe products.

In the face of the potential of this phenomenon, several economic, logistical, and spatial barriers inhibit the possibility of small and medium restaurants implementing these alternative procurement systems. Specifically, while self-production brings economic benefits for a precise segment of the restaurant sector, it can only partially help in boosting the local economy and creating networks among different stakeholders of the local food system. Due to this situation, a great portion of the regional restaurants would be still exposed to price fluctuations of products in the local food market. In order to explore possible solutions to cope with this issue, further studies should investigate the point of view of actors located at different levels of the supply chain to identify their motivations and to figure out alternative ways to foster the creation of commercial and social networks between the restaurateurs and other actors of the local foodscape. In particular, the implementation of short supply chains would imply an analysis of the logistical, spatial, and legal barriers related to the development of these activities.

Conclusions

The research highlights how the revival of traditional products does not follow a search for cultural authenticity (Umbach and Humphrey, 2017). It suggests reading the phenomenon via an exploration of the link between the gastronomic offering and the specificity of the local agri-food market. The research has therefore highlighted how this relaunch develops from a demand for healthy and natural foods rather than cultural appropriation, and that, based on the specificities of the local market, this fosters the creation of alternative supply strategies to cope with the poor quality of ingredients, price fluctuations, and discontinuity of the supply.

In this sense, the research suggests not overestimating, outside the Global North, the importance of intangible factors such as post-modern disorientation, the influence of global gourmand trends, or consumers’ ethical drivers in the revival of local and traditional production. Rather, the research points to other tangible factors linked to the technological and logistical conditions of the trade and safety of food served in order to understand why local and traditional foods are rediscovered and popularized.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Prior to each interview, informed consent was obtained, as recommended by the code of ethics of the American Anthropological Association, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Gastronomic Sciences.

Author Contributions

DZ: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. MF: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—review, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was part of the SASS—Sustainable Agri-Food System Strategies research project funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research (Project code: H42F16002450001).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Slow Food Kenya, specifically to the members who assisted us during fieldwork: John Kariuki, Jane Njeri, Samson Kiiru, Njeri Githieyah, Elphas Masanga, and Ruth Migwi.

References

Abukutsa-Onyango, M., Mwai, G. N., Otiato, D. A., and Onyango, J. (2007). “Urban and peri-urban indigenous vegetables production and marketing in Kenya,” in Report presented to the 6th Thematic Meeting of the IndigenoVeg Project. (Maseno: Maseno University).

Addor, F., and Grazioli, A. (2002). Geographical indications beyond wines and spirits. A roadmap for a better protection for geographical indications in the WTO/TRIPS Agreement. J. World Intellect. Prop. 5, 865–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1796.2002.tb00185.x

Adeka, R., Maundu, P., and Imbumi, M. (2009). Significance of african traditional foods in nairobi city markets, Kenya. Acta Hortic. 806, 451–458. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.806.56

Aworh, O. C. (2018). From lesser-known to super vegetables: the growing profile of African traditional leafy vegetables in promoting food security and wellness. J. Sci. Food Agric. 98, 3609–3613. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8902

Barstow, C., and Zocchi, D. M. (2018). The Ark of Taste in Kenya. Food, Knowledge and History of the Gastronomic Heritage. Bra: Slow Food Editore

Bégin, C. (2016). Taste of the nation: the New Deal search for America’s food. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. doi: 10.5406/illinois/9780252040252.001.0001

Bessiere, J., and Tibere, L. (2013). Traditional food and tourism: French tourist experience and food heritage in rural spaces. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 3420–3425. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6284

Bett, H. K., Musyoka, M. P., Peters, K. J., and Bokelmann, W. (2012). Demand for meat in the rural and urban areas of Kenya: a focus on the indigenous chicken. Econ. Res. Int. 2012, 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/401472

Broadway, M. (2015). Implementing the slow life in Southwest Ireland: a case study of clonakilty and local food. Geogr. Rev. 105, 216–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2014.12067.x

Chemeltorit, P., Saavedra, Y., and Gem, J. (2018). Food traceability in the domestic horticulture sector in Kenya: An overview. Practice brief 005. Wageningen: Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation

Curtis, K. R., and Cowee, M. W. (2009). Direct marketing local food to chefs: chef preferences and perceived obstacles. J. Food Distrib. Res. 40, 26–36. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.99784

De Chabert-Rios, J., and Deale, C. S. (2018). Taking the local food movement one step further: an exploratory case study of hyper-local restaurants. Tour. Hosp. Res. 18, 388–399. doi: 10.1177/1467358416666137

Dolan, C. S. (2007). Market affections: moral encounters with Kenyan fairtrade flowers. J. Anthropol. 72:239–261. doi: 10.1080/00141840701396573

Du Rand, G. E., Heath, E., and Alberts, N. (2003). The role of local and regional food in destination marketing. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 14, 97–112. doi: 10.1300/J073v14n03_06

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., and Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633

Foeken, D., (ed.). (2006). To Subsidise my Income: Urban Farming in an East-African Town. Leiden: Africa Studies Centre.

Fontefrancesco, M., Zocchi, D. M., and Corvo, P. (2020). Quanto la multiculturalità appiattisce l’offerta. Dinamiche culturali e sviluppo merceologico alimentare nei mercati della contea di Nakuru, Kenya. Dada Riv. Antropol. Post-glob. 1, 129–156.

Frash, R. E., DiPietro, R., and Smith, W. (2015). Pay more for mclocal? examining motivators for willingness to pay for local food in a chain restaurant setting. J. Hosp. Mark Manag. 24, 411–434. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2014.911715

Fusté-Forné, F. (2019). Seasonality in food tourism: wild foods in peripheral areas. Tour. Geogr. 21, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1558453

Gakobo, T. W., and Jere, M. G. (2016). An application of the theory of planned behaviour to predict intention to consume African indigenous foods in Kenya. Br. Food J. 118, 1268–1280. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-10-2015-0344

Gido, E. O., Ayuya, O. I., Owuor, G., and Bokelmann, W. (2017). Consumption intensity of leafy African indigenous vegetables: towards enhancing nutritional security in rural and urban dwellers in Kenya. Agric. Econ. 5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40100-017-0082-0

Ginani, V. C., Araújo, W. M. C., Zandonadi, R. P., and Botelho, R. B. A. (2020). Identifier of Regional Food Presence (IRFP): a new perspective to evaluate sustainable menus. Sustainability 12:3992. doi: 10.3390/su12103992

Gotor, E., and Irungu, C. (2010). The impact of bioversity international’s African leafy vegetables programme in Kenya. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 28, 41–55. doi: 10.3152/146155110X488817

Guptill, A. E., Copelton, D. A., and Lucal, B. (2016). Food and Society: Principles and Paradoxes. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Home, R., Oehen, B., Käsmayr, A., Wiesel, J., and Van der Meulen, N. (2020). The importance of being local: the role of authenticity in the concepts offered by non-themed domestic restaurants in Switzerland. Sustainability 12:3907. doi: 10.3390/su12093907

Ilbery, B., and Maye, D. (2005). Food supply chains and sustainability: evidence from specialist food producers in the Scottish/English borders. Land Use Policy 22, 331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.06.002

Ilbery, B., Morris, C., Buller, H., Maye, D., and Kneafsey, M. (2005). Product, process and place: an examination of food marketing and labelling schemes in Europe and North America. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 12,116–132. doi: 10.1177/0969776405048499

Inwood, S. M., Sharp, J. S., Moore, R. H., and Stinner, D. H. (2009). Restaurants, chefs and local foods: insights drawn from application of a diffusion of innovation framework. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 177–191. doi: 10.1007/s10460-008-9165-6

Kim, S., and Iwashita, C. (2016). Cooking identity and food tourism: The case of Japanese udon noodles. Tour Recreat Res. 41, 89–100. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2016.1111976

Kingori, A. M., Wachira, A. M., and Tuitoek, J. K. (2010). Indigenous chicken production in Kenya: a review. Int J Poult Sci. 9, 309–316. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2010.309.316

Knaepen, H. (2018). Making markets work for indigenous vegetables towards a sustainable food system in the lake Naivasha basin, Kenya. ECDPM Discussion paper, 230. Amsterdam: ECDPM.

Kocaman, E. M. (2018). A cross-cultural comparison of the attitudes of employees towards the presence of traditional foods in business menus. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 13, 10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2018.05.002

Kyule, N. M., Mwangi, J. G., and Nkurumwa, O. A. (2014). Indigenous chicken marketing channels among small-scale farmers in Mau-Narok division of Nakuru County, Kenya. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Entrep. 1, 55–65.

Lane, C. (2011). Culinary culture and globalization. An analysis of British and German Michelin-starred restaurants. Br. J. Sociol. 62, 696–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2011.01387.x

Martinez, S. M., Hand, M., Da Pra, S., Pollack, K., Ralston, T., Smith, S., et al. (2010). Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts and Issues. Economic Research Report Number 97. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Maundu, P., and Imbumi, M. (2003). “The food and food culture of the peoples of East Africa (Kenya,Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia),” in Encyclopaedia of Foods and Culture, vol. 1. Eds S. H. Katz (New York, NY: Charles and Scribner’s Sons), 27–34.

Maundu, P., Kabuye, C. H. S., and Ngugi, G. W. (1999). Traditional Food Plants of Kenya. Nairobi: National Museum of Kenya.

Maundu, P. M. (1997). “The status of traditional vegetable utilization in Kenya,” in Genetic Resources of Traditional Vegetables in Africa: Conservation and Use, ed. L. Guarino (Rome: IPGRI), 66–75.

Meldrum, G., and Padulosi, S. (2017). “Neglected no more: leveraging underutilized crops to address global challenges,” in Routledge Handbook of Agricultural Biodiversity eds. D. Hunter, L. Guarino, C. Spillane, P.C. McKeown (London: Taylor and Francis Ltd), 298–310. doi: 10.4324/9781317753285-19

Miele, M., and Murdoch, J. (2002). The practical aesthetics of traditional cuisines: slow food in tuscany. Sociol. Ruralis 42, 312–328. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00219

Mnguni, E., and Giampiccoli, A. (2019). Proposing a model on the recognition of indigenous food in tourism attraction and beyond. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 8, 1–13.

Montefrio, M. J. F., De Chavez, J. C., Contreras, A. P., and Erasga, D. S. (2020). Hybridities and awkward constructions in Philippine locavorism: reframing global-local dynamics through assemblage thinking. Food Cult. Soc. 23, 117–136. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2020.1713428

Murdoch, J., Marsden, T., and Banks, J. (2000). Quality, nature, and embeddedness: some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector. Econ. Geogr. 76, 107–125. doi: 10.2307/144549

Murphy, J., and Smith, S. (2009). Chefs and suppliers: an exploratory look at supply chain issues in an upscale restaurant alliance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 28, 212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.07.003

Musinga, M., Kimenye, D., and Kivolonzi, P. (2008). The Camel Milk in Kenya. Nairobi: Resource Mobilization Centre.

Mwangi, A. M. (2002). Nutritional, Hygiene and Socio-Economic Dimensions of Street Foods Urban Areas: The Case of Nairobi. (Ph.D. thesis). Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands.

Mwema, C., and Crewett, W. (2019). Institutional analysis of rules governing trade in African Leafy Vegetables and implications for smallholder inclusion: case of schools and restaurants in rural Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 67, 142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.004

Namkung, Y., and Jang, S. (2017). Are consumers willing to pay more for green practices at restaurants? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 41, 329–356. doi: 10.1177/1096348014525632

Nduko, J. M., Matofari, J. W., Nandi, Z. O., and Sichangi, M. B. (2017). Spontaneously fermented Kenyan milk products: a review of the current state and future perspectives. Afr. J. Food Sci. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.5897/AJFS2016.1516

Neugart, S., Baldermann, S., Ngwene, B., Wesonga, J., and Schreiner, M. (2017). Indigenous leafy vegetables of Eastern Africa — a source of extraordinary secondary plant metabolites. Food Res. Int. 100, 411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.02.014

Ngugi, I. K., Gitau, R., and Nyoro, J. K. (2007). Access to High-value Markets by Smallholder Farmers of African Indigenous Vegetables in Kenya, Regoverning Markets Innovative Practices Series. London: IIED.

Oloo, B. O., Mahungu, S., Gogo, L., and Kah, A. (2017). Design of a HACCP plan for indigenous chicken slaughter house in Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 17, 11616–11638. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.77.16765

Owuor, B. O., and Olaimer-Anyara, E. (2007). The value of leafy vegetables: an exploration of African folklore. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 7, 33–38.

Ozturk, S. B., and Akoglu, A. (2020). Assessment of local food use in the context of sustainable food: a research in food and beverage enterprises in Izmir, Turkey. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 20:100194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100194

Pereira, L. M., Calderón-Contreras, R., Norström, A. V., Espinosa, D., Willis, J., Guerrero Lara, L., et al. (2019). Chefs as change-makers from the kitchen: indigenous knowledge and traditional food as sustainability innovations. Glob. Sustain. 2:e16. doi: 10.1017/S.2059479819000139

QSR International (2019). NVivo qualitative data analysis Software Version 12.5.0. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International.

Raschke, V., and Cheema, B. (2008). Colonisation, the new world order, and the eradication of traditional food habits in East Africa: historical perspective on the nutrition transition. Public Health Nutr. 11:662–674. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001140

Rinaldi, C. (2017). Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development : a multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability 9:1748. doi: 10.3390/su9101748

Roy, H., Hall, C. M., and Ballantine, P. (2016). “Barriers and constraints in the use of local foods in the hospitality sector,” in Food Tourism and Regional Development: Networks, Products and Trajectories, eds C.M., Hall, S., Gössling (Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge), 255–272.

Shackleton, C. M., Pasquini, M. W., and Drescher, A. W. (2009). African indigenous vegetables in urban agriculture. London: Earthscan. doi: 10.4324/9781849770019

Sharma, A., Gregoire, M. B., and Strohbehn, C. (2009). Assessing costs of using local foods in independent restaurants. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 12, 55–71. doi: 10.1080/15378020802672089

Sharma, A., Moon, J., and Strohbehn, C. (2014). Restaurant’s decision to purchase local foods: Influence of value chain activities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 39, 130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.01.009

Sims, R. (2010). Putting place on the menu: The negotiation of locality in UK food tourism, from production to consumption. J. Rural Stud. 26, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.09.003

Starr, A., Card, A., Benepe, C., Auld, G., Lamm, D., Smith, K., et al. (2003). Sustaining local agriculture Barriers and opportunities to direct marketing between farms and restaurants in Colorado. Agric. Hum. Values 20, 301–321. doi: 10.1023/A:1026169122326

Timothy, D. J., and Ron, A. S. (2013). “Heritage cuisines, regional identity and sustainable tourism,” in Sustainable Culinary Systems: Local foods, Innovation, and Tourism and Hospitality eds. C. M. Hall, S. Gössling (London: Routledge), 275–289.

Tregear, A., Arfini, F., Belletti, G., and Marescotti, A. (2007). Regional foods and rural development: the role of product qualification. J. Rural Stud. 23, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.09.010

Source link